Lights on, lights off. Is Martin Creed in the house? Enigmatic exchanges between nameless prisoner and jailer. Pinter, perhaps? Unexpected explosions into the space of ludicrous objects and strange creatures. Ahoy there, Ionesco! A disembodied mouth groaning and licking its lips expectantly. Oh, we were waiting for you, Beckett. Channelling Artaud to bring us a total theatre; holding us captive in a dark space that is activated by surreal characters, startling interventions, and a wicked gallows humour. Shunt, perchance?

Ah yes, Shunt. Not quite, but more or less. An Execution (by invitation only) is a show by Shunt co-founder Gemma Brockis. It was first made 15 or so years ago, and was presented in the dark and dank cellars of Shunt Vaults, where the notion of creating a show in a cell in which total blackout plays a key role would perhaps have been an obvious choice. Now we are in CPT’s main space, herded into a square white-cube cell which has been constructed within the black box. But there are still trains – below rather than above, the sound of their rumbling through tunnels merging with the howl of sirens and horn hoots from the traffic outside, adding an extra layer to an already rich soundscape.

Seeing this show here and now at CPT, it is startling to realise that many in the audience would have been too young to have ever attended Shunt’s trailblazing venue under the railway arches of London Bridge (and certainly much, much too young to even know that before that, there was Bethnal Green). It is also odd, for an old hand like me, to think that for theatre’s emerging artists, Shunt are part of the canon – on the syllabus, so to speak. And despite – perhaps because of – its measured absurdism, the show feels like a theatre classic of a certain European kind.

It is inspired and informed by Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, which takes place in a prison and gives us the final days of a man who is imprisoned and sentenced to death for ‘gnostical turpitude’. Unable to become part of the world around him, the prisoner is described by Nabokov as ‘impervious to the rays of others… as of a lone dark obstacle in this world of souls transparent to one another’. This notion of being somehow guilty for not fitting in, not being ‘normal’ enough, is a tune taken up and played throughout mid-twentieth-century literature and drama. Camus’ L’Etranger. Almost everything by Kafka. And yes, not only Beckett, Pinter, and Ionesco but also Albee, Pirandello, and Jodorosky.

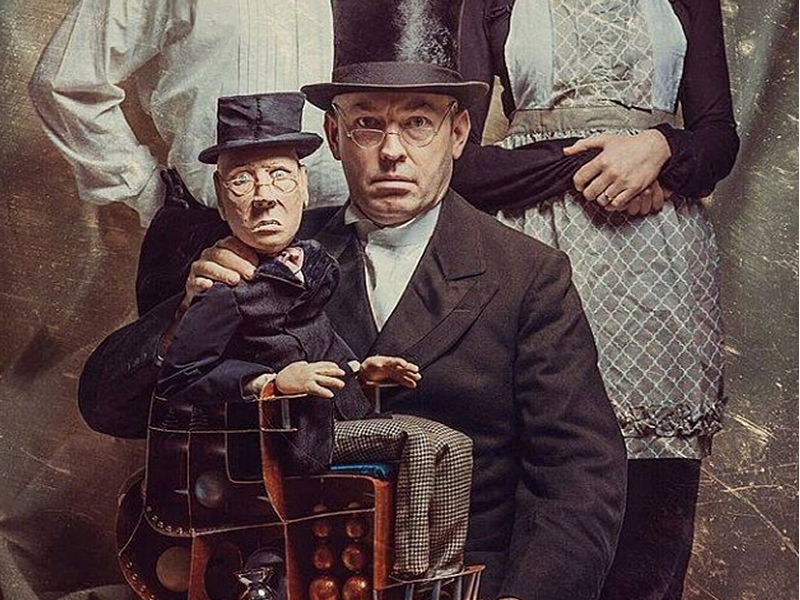

But enough of all that – back to what we have on-hand. We, the Peeping Toms, the ghosts, the flies on the wall, are sat tightly packed on low benches, on two sides of the cube. There’s the prisoner (Greg McLaren), something of a blank slate, wielding a graphite pencil with which he scratches words (‘undersea’ is the only one I can make out) and marks out spiralling mandalas – webs almost – on the white floor. There are three others who come and go: a key-jangling jailer with a hissy portable transistor radio (Tom Lyall); a bumbling barrister who’s not sure if he’s brought the right bag (Simon Kane); and a sharply dressed female visitor (Shamira Turner), who plays a rather distracted and unloving wife, who clearly wants to keep visits to a minimum as she has better things to be getting on with in the outside world. There are two other characters: the spiderwoman, who comes and goes in numerous forms and modes; and a Deus Ex Machina golf-club-swinging executioner, who is everything the other men fail to be, a confident and assured man of the world offering tips for a good clean beheading.

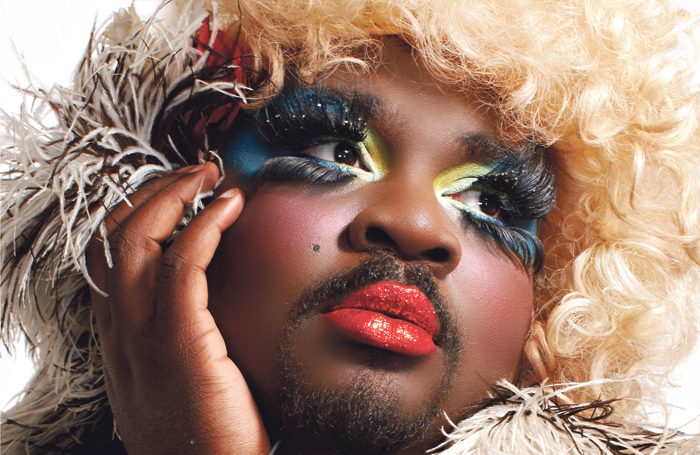

The audience are not brought into the action in any obviously interactive way, but their presence is acknowledged, usually as physical obstructions in the space. Feet on the floor are drawn around. People are stepped over to reach the hot-lipped mouth of spidery desire, which spits out the tenderly offered boiled sweets, chews the celery in a bemused manner, but goes wild for the baby mice.

This (like most things that come out of the Shunt collective) is a show in which scenography and dramaturgy are inextricably linked. Light and sound aren’t illustrative add-on extras, they drive the narrative. Paper walls become the site for a strange shadow play, or are ripped to reveal enigmatic physical actions happening just outside the cell, on the edge of our peripheral vision. The stark white overhead light suddenly cuts or shifts to a blood-red that bathes the walls. Whimsical snatches of vintage dance music are heard, and a blast of Edith Piaf.

Repetition, with twists, is a key element. Doors open, doors close. People arrive, people leave. At no point is this a naturalist drama, but the skim of naturalism at the start is soon torn to shreds, and the boundary between (pseudo) reality and fantasy breaks down as actions and images become more abstracted. We are enmeshed in a web of dreams, desires and terrors. Time passes. And now, the time has come to face the final curtain. The prisoner has departed. No more lawyers or executioners. The jailer remains. It is an oft-repeated truth that the jailers are the true, permanent prisoners of our jails. No escape, even if he wanted it. But what is it he really, really wants? The eight-legged object of his desire manifests herself in a new incarnation. The jailer waltzes with the spiderwoman. (Properly waltzes, in time, a fast waltz of neat natural turns circling the space. This sort of attention to detail pleases me.)

An Execution (directed by Gemma Brockis and created with Michael Regnier) is not a perfect piece of theatre – although it’s a very good one. The script dips at times, and feels like it could do with tightening up here and there. The dark humour wins through for the most part, but occasionally misfires, or doesn’t quite hit home strongly enough. Overall, though, the brilliantly-executed performances from all four actors, and the rich onslaught of surprising and entertaining visual images that unfold, are more than enough to keep us enthralled in our captivity.