So, here I am in Edinburgh, on the eve of the opening of the Fringe – it officially kicks off tomorrow, Friday 3 August. Today was planned as a quiet, settling in sort of day. Two shows booked to review (some have opened early), and maybe a bit of networking and organising. This is how it went…

11.00: I’m at the Pleasance Courtyard which is relatively quiet and calm – the Fringe hasn’t really started yet, after all. I’m here to see a children’s show, Ripstop Theatre’s Luminous Tales, which is part of the Escalator East to Edinburgh programme. I have high hopes, as Escalator is usually a mark of quality, and the show comes tagged as a Norwich Puppet Theatre production – or endorsement, at least – hard to tell for sure what the relationship actually is. It’s a bit of a disappointment – and worryingly the puppetry is below-par. I’m left feeling a bit confused, and feel the need to phone Total Theatre reviews editor Beccy Smith for a quick counselling session. She advises that I should write the review that needs to be written, regardless – so that’s what I’ll do (it’ll pop up in the reviews section soon, folks). Not a very auspicious start to my Fringe experience…

12.40 Still at the Pleasance. Now I’m off to see Pete Edward’s FAT, another Escalator show, billed as ‘the multi-media journey of a gay disabled man in search of his heart’s desire’. This one is good – thankfully. I’m thinking it might be time for lunch, but a persistent person with a bunch of flyers is insisting that I need to See Exterminating Angel at 14.00. He offers me a free ticket. I point out that if I wanted to see it for free, I’d go and get myself a press ticket, and anyway I am pretty sure I’ve already allocated another Total Theatre reviewer to see this one. He looks at me with big soulful brown eyes and shrugs. If he’d have carried on with the sales pitch I’d have walked on, but there’s something about that shrug. I take the ticket from his hand…

14.00 Pleasance Above, Exterminating Angel. Not a reworking of the Bunuel film, but inspired by it, with a dash of Maeterlinck’s The Blind to boot. An improvised show, the action set around a never-ending dinner party – the outcome is never the same is the USP. How much is improvised, and how they go about setting their improv rules I have no idea – but it’s good, very good. Dangerously funny, edgy, and working the balance between the mundane and the surreal very cleverly. I’m glad I went, so thank you tall dark handsome stranger.

15.30 After a hurried lunch, it’s off to Fringe Central to meet the press (department). Media passes for me and the Total Theatre reviewing team sorted; spreadsheets of venue and show contacts acquired; access to computer and office facilities organised.

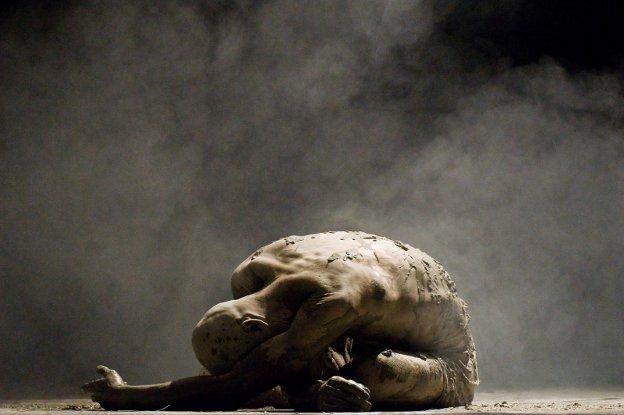

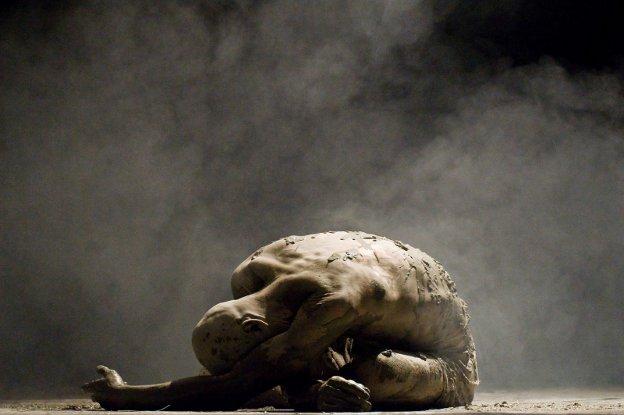

16.40 I’m now at C Nova – one of the newer venues of the ever-expanding C Venues empire – for Remor, a show in a box by Spanish company Res de Res. Eleven minutes of intense non-verbal performance in a mock prison cell. Take no prisoners performance you might say…

17.00 Ah, a press launch! I’ve managed to miss the Zoo Venues one but make it to the Gilded Balloon for wine and canapés. A number of keen theatre-makers try to sell me their shows: there’s the one about the wife of a porn addict and how she got divorced and got a life (‘it’s based on a true story – and there aren’t many Fringe shows by and about middle-aged people’), the one by two Cornish rappers and a Casiotone (‘er, are you busy? I suppose we should be telling you about our show as you’ve got a reviewer’s badge on. We’re from Cornwall…’), and the one with a gun wearing a condom on the flyer (‘some people find the image disturbing, but don’t mind that, read the back!”) which is the proud winner of the Sir Michael Caine award for new writing. Luckily, I’m rescued by Steve Forster (Escalator’s ever-cheerful press officer), who tells me about something I genuinely do want to see – Thread, the new show by Nutshell, creator of last year’s site-specific success Allotment, which is also back for a one-week run. He also reminds me to come along to the Hunt & Darton Café, which is, yes, a café – but a café as ongoing art project. Kind of like the late-lamented Forest Café but will less lentils, perhaps?

18.00 Somehow – and Lord knows how this happened – I have found myself agreeing to join a makeshift ‘community choir’ being put together for h2dance’s interactive/immersive dance-theatre show Say Something at Summerhall. I tried grumbling that it was all a bit of a busman’s holiday, given that I’ve opted out of paid work with my company Ragroof Theatre in order to dedicate August to my Total Theatre duties at the Fringe, but nevertheless, here I am crawling on the floor and singing ‘la la la la nananana-nanu’ as if my life depended on it. ‘So, see you at tomorrow’s rehearsal’ says h2dance’s Heidi Rustgaard at the end of the evening, and ‘yes’ I say. So that it that….

23.00 Home – or at least home to the place that will be my home for the coming month. Gosh, it hasn’t even started yet and I feel like I’ve been here forever. Has it really been just one day?

www.edfringe.com