So, why are some things in the Festival and some in the Fringe? This was asked of me by an interested ‘non-artist’ friend visiting Brighton in the hectic month of May. Once, the answer would have been straightforward: the Brighton Festival is curated, and artists are invited to take part and paid a performance and/or commissioning fee, whilst the Fringe (like its big sister in Edinburgh) is a free-for-all. It’s uncurated, and anyone can take part – people wanting to show work in whatever medium find their own venues, and make what they can from negotiated fees or (more usually) door splits with those venues.

But things are less clear these days. For example, in 2012 one of the biggest successes of ‘the festival’ wasn’t an actual Festival event but a Fringe one – Dip Your Toe. And to further blur the boundaries, this was a curated, commissioning venture by a consortium of three organisations: the Brighton Fringe, the Nightingale Theatre, and the Marlborough Theatre – and it ended up as listed in both the Fringe and the Festival programmes, for various and sundry reasons. So, what was it? Six bespoke mock-Victorian bathing machines (large huts on wheels) were created and customised. In some cases, one artist or company received a commission to design and commandeer a ‘hut’ for their exclusive use. In this category came Karavan Ensemble’s A Small Museum of Displaced Sea, which operated as both installation and ensemble performance, inspired by local history and older people’s memories of Brighton; Seth Kriebel & Zoe Bouras’s Vivascope, a contemporary take on the camera obscura; and Grist to the Mill’s Kissing the Gunner’s Daughter, a peepshow soundscape-and-animation piece reported on in the last Total Theatre Magazine. There were also a number of shows that had temporary occupation of a bathing machine, these including Inconvenient Spoof’s The Terrible Shaman, a terrifyingly funny and irreverent look at anthropological adventuring, exotic religious practices, and the myth of the noble savage.

Dip Your Toe was created in tandem with Lone Twin’s The Boat Project, in celebration of the maiden voyage of said boat, which was created from donated wood – a kind of floating repository of memories. The (main Festival event) sail-by turned out to be a little bit of an anticlimax as the boat is not particularly large or spectacular. Seeing it moored at the nearby Brighton Marina was also disappointing – no signage, and no awareness of the project or interest from any of the local sailing community meant that it was nigh on impossible to locate, and when it was located, there was nothing to mark it out from its neighbouring vessels. It is hard to know if this is down to the company or to the Brighton Festival, but it did feel like something of a non-event. However, there seem to be a whole load of interesting events and initiatives circulating around the Boat Project – for example, I discovered some interesting sound-art works being broadcast on something called Boat Radio, hosted bywww.folkestonefringe.com Worth a listen!

But back to Brighton. Not content with organising the massive off-site project that was Dip Your Toe, the Nightingale also had a fully-fledged and properly curated indoor theatre programme on its home ground, a small but perfectly formed theatre space above the Grand Central pub next to Brighton Station. Treats here included a showing of Nassim Soleimanpour’s White Rabbit, Red Rabbit – one of the big hits of the Edinburgh Fringe 2011. The USP for this show is that the author wants to be present but is absent (stuck in homeland Iran) and the one actor performing on his behalf has not seen the script before he/she takes to the stage and opens the envelope. I was lucky enough to get Sue MacLaine (of Still Life and Sid Lester fame) as the actor on the night I went. Hers was a tender and responsive performance that really highlighted the poignancy of the absence/presence pairing of author and actor – and funny to boot. I will remember her galloping ostrich until the day I die…

Another enjoyable evening at the Nightingale was a double-bill of two emerging but highly skilled and already firmly established companies, Touched Theatre and Moved to Stand. Touched Theatre’s Headcase employed the very talented Yael Karavan and Annie Brooks in the service of a story about a goldfish and a girl, exploring mental health issues in young people in a playful and effective way – a lovely fusion of puppetry, physical performance and film. Move to Stand’s Kin trod the delicate ground between new writing and physical theatre. I was reminded of Analogue Theatre in both the structure of the piece and the subject matter – Kin investigates language, communication, personal relationships, and the tug between competing desires. Ultimately, the piece is about sacrifice – the sacrifice of individual needs, and the sacrifice of one life in the creation of another. The performance skills of all four in the team (three actors and a musician) are unquestionably excellent, and the company are one to watch – but I personally struggled with some aspects of the story. (Hard to discuss without giving the game away – let me just say that I didn’t really suspend disbelief at the moment of tragic denouement!)

Elsewhere in the Nightingale programme were Brighton luminaries Tim Crouch, The Two Wrongies, Boogaloo Stu, and Circa69 (one of Simon Wilkinson’s vehicles, others including Junk TV and Il Pixel Rosso, his ongoing collaboration with Silvia Mercuriali of Rotozaza). A surprise hit for the Nightingale was another off-site show, the interactive audio piece If I Ruled the World by Nova Pitch, reviewed here by Miriam King.

Across the town from Nightingale, a couple of newer ventures were making their mark. TOM (The Old Market) has been around a while, but in recent times it has been rebranded and taken over by the Stomp boys (Yes/No People), and for 2012 had some real treats on offer, including an extended version of Blind Summit’s The Table (reviewed by Total Theatre online at the Edinburgh Fringe 2011, and again in print at the London International Mime Festival 2012). So yes – the Fringe attracts big stars too! Conversely, the Festival featured a number of not-too-well-known artists in its mix – perhaps there is an argument for supporting artists at all stages of their careers but I’d argue (as I have done in the past) that exposing an artist to the scrutiny that being programmed into a large-scale international festival brings is not necessarily for the best. But let’s move on…

And so then there were the pop-up Fringe venues – many and various, but including The Warren, a venture right in the heart of Brighton, programmed by the team that run Upstairs at Three & Ten, a successful year-round theatre-above-a-pub venue with an eclectic programming policy. The Warren had an exciting selection on offer in May, including the wonderful, wordlessTranslunar Paradise by Theatre Ad Infinitum (who will be taking their hit show back for a second year at Edinburgh in 2012).

Of course that’s the whole thing about Fringe festivals – a venue can be anything, anywhere. A church, say. A little off the beaten track came Feral Theatre’s production Triptych, set in what locally is called Small St Peter’s Church, on the edge of Preston Park. This still-working church – a beautiful Norman stone building which has survived fire and flood and all sorts throughout the years. I’ll admit to a little bit of trepidation when I read thatTriptych fused circus and storytelling, and had an ecological theme. It could have been a holier-than-thou disaster, but was nothing of the sort.

Emily Laurens, Rachel Porter, and Persephone Pearl are our three writer/storytellers. Each uses the specific personal skills she has at her service for both her own and her companions’ stories. Emily is first, with a heartbreaking story about the last of the Eskimo Curlews (an Artic bird whose numbers are in serious decline), playing on the differing languages of science, poetry, modern reportage and traditional storytelling in the telling of tales. Her story is illustrated with beautiful shadow puppetry by Rachel Porter.

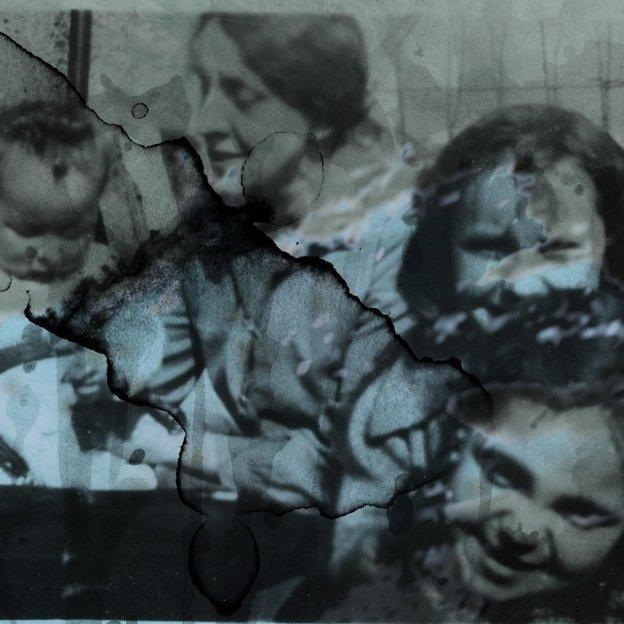

Rachel’s own story introduces us to Papusza, a female Roma poet, and describes itself as ‘a poetic interpretation of fragments of her life’. We see Papusza tugged hither and thither, surrounded by torn pages, hearing voices, endlessly repeating phrases, as she struggles with accusations of madness and the disapprobation of society – ‘no one understands me, only the forest and the river’.

Storyteller three Persephone Pearl is an aerialist. She uses her silks to tell a tale of life in the trees – not the first time this has been done (see, for example, numerous works by Scarabeus) but she does it well – very well. The Twyford Down anti-motorway campaign of the 1990s brought the world images of protesters of all sorts – from weather-beaten crusties to hardcore hippies to veteran lefties to newly converted middle-class ecologists – banding together to stop the destruction of ancient forest to widen the M3. Persephone focuses on one character – an idealistic young woman, experiencing the politics of protest for the first time – and tells the story of her initiation into the protest. Silks are climbed and clung from, wound up to become tree-top sleeping ‘pods’ or used to ensnare our heroine. There are moments when the text delivery is a little shouty (how to play loud and outraged without the shoutiness, and whilst performing a delicate aerial manoeuvre, is a challenge, I am sure) and I would see spoken text delivery as a focus of future work for all the company. But this is all stuff that can, and will, improve with time. What is already in place is great, and their understanding of what makes good theatre is exemplary. Form and content marry well, and I particularly enjoy the way they pass the baton between them, moving the storytelling hand-to-hand from one to the other, drawing each other in and out of the action. I also love the merging and mixing of live and recorded song and sound, orchestrated by the fourth onstage performer, musician and multi-instrumentalist Tom Cook.

Meanwhile, back in the main Festival for something completely different: Spymonkey are to be found at the red-plush Theatre Royal with Oedipussy, an irreverent look at Greek drama’s most famous errant son – directed with aplomb by Kneehigh’s Emma Rice, who describes Spymonkey as ‘the greatest conceptual and physical comedians working in this country’ and ‘the true inheritors of vaudeville’. Well, can’t argue with that.

Spymonkey are indeed terrific. The clowning skills are superb – all four company members are wonderful, but I’m always drawn most strongly to Petra Massey, perhaps because female clowns of this calibre are so rare in the UK. The humour, as always, is deliciously tasteless. (Cue Aitor and the Leper Song: leprosy isn’t funny – oh yes it is!) Stephan Kreiss gets the starring role (yes! at last!), Toby Park gets to really enjoy making music onstage, and Lucy Bradridge’s costume design picks up on the Bond-and-Barbarella vibe beautifully – 60s sci-fi metal headdresses, sparkly silver suits, and ludicrous Cleopatra eyeliner. And, as with previous show Moby Dick, there is this odd and interesting realisation that these clown explorations of classic tales actually bring us closer to the real truth of the stories in question than many a serious interpretation. Is there a ‘but’? A completely honest response is that marvellous though it all is, this Spymonkey production didn’t, for me, quite match up to the extraordinary and wonderful success of Moby Dick, which was created in collaboration with ‘art of laughter’ genius Jos Houben (founder member of Complicite). For once, I found the postmodern cum Frankie Howard-ish stepping in and out of the action in Oedipussy just a trifle irritating, and the physical gags not quite as breathtakingly funny in this show as in the previous production. But nevertheless a good night out, filled with fun and frolics.

More main festival: War Sum Up, Hotel Pro Forma’s collaboration with the Latvian National Opera, uses Anime/Manga inspired animation in interaction with live performance in a way that can perhaps best be described as a work of moving sculpture. There are echoes for me of Heiner Goebbels’ work. The piece investigates the nature of war, and specifically the archetypal roles of Soldier, Warrior and Spy, who are all manipulated by the Gamemaster. Yes, it sounds (and indeed looks) like live video-gaming. The music is an extraordinary amalgam of opera, electronica, and what the company call ‘chamber pop’. I haven’t quite heard or seen anything like it before, and salute the artists for creating such a visually and aurally rich work, although I have to confess that not a lot remained with me afterward – it felt all very much like a vivid dream, intense at the time, but fading quickly. I was not surprised to learn that international collective Hotel Pro Forma is led by a visual artist.

I also got to see DV8’s renowned production Can We Talk About This?. I am possibly in a minority of one, but it didn’t move or inspire or excite me one little bit. It went to the head, not to the heart. Cleverly pieced together verbatim theatre mulched with some great choreography performed by exceptionally skilled dancers – and yes, Lloyd Newson is a brave man to tackle the tangle of issues around freedom of speech, multiculturalism, forced marriage, and Islamism in the West – but I felt preached to, and if ever there was a case of preaching to the converted, this was it!

The theatre programme of the Brighton Festival also included numerous shows already reviewed or appraised by Total Theatre, either on this website or in print in Total Theatre Magazine Volume 24 Issue 02. These include the festival’s flagship production The Rest is Silence, by dreamthinkspeak (the subject of The Works in the print magazine); a multimedia installation and theatre piece set in an old fruit market, Land’s End by Berlin; Motor Show, an outdoor work by David Rosenberg and Frauke Requardt, commissioned by Without Walls; and Bootwork’s boyish homage to the film Predator.