A group of men stand in a line, each holding a sheet of paper with his name written on it. Lou. David. Ruben. Sukrim. Gabriel. Marcelo.

Lou and David, tall and broad shouldered, look like retired British soldiers, which they are. Royal Marines. They look and sound like ex-Marines, but they are now both PhDs; one a psychologist specialising in war trauma, and one a special needs teacher who is also an expert on the philosophy of colour. Sukrim is much shorter. He’s a Gurkha who was trained in jungle warfare in Brunei, has travelled the world, and was brought over to fight in the Falklands. The Malvinas. Ruben is a survivor of the sinking of the General Belgrano, having spent 41 hours adrift in the South Atlantic on a raft, witnessing death all around him. He is also the founder of the Beatles tribute band Get Back Trio, who have played at The Cavern in Liverpool. Gabriel was a conscript to the Argentine army who fought in the Battle of Wireless Ridge. He became a lawyer, and he also lectures on the Malvinas in Argentinean schools. Marcelo was also a conscript soldier – like the other Argentines, just 19 years old when called to war. He’s shorter and broader than his two countrymen, with a muscly torso. He led a troubled life post-war, although saved himself through sports training, and now takes part in triathlons. He talks of the fear they had of the Gurkhas, who were rumoured to be hacking Argentinians to pieces and eating their ears.

Lou is telling us the story of returning to Buenos Aires, many years after the Falklands War ended, to make this show. He talks about being met at Buenos Aires airport not by an Argentine holding a gun to his head, but by a smiling person holding a piece of paper bearing his name. The rehearsals took longer than the war did, he says, and we chuckle. 74 days, that’s how long the war lasted. He’d been garrisoned on the Falklands, before the war broke out, and he’d been taken prisoner, then later returned there to fight on, and then he’d gone back for the 25-year reunion. But now he was heading to Argentina to work with theatre-maker Lola Arias – who is Argentinean, and was just just 6 years old in 1982 when the Falklands War / Guerra de Las Malvinas (the surtitles studiously switch between the two) took place. But she knew all about it. As we learn in the play, Argentinean children are taught about the Malvinas in school, and learn to sing the March of the Malvinas. It is very much a current political issue. Unlike English schoolchildren, who are taught nothing about the war or the history behind it, or of Argentine’s current position – and let’s face it, is there anybody out there who gives two hoots about the Falklands nowadays?

David has a bit of a penchant for dressing up in ladies’ clothing to entertain his mates. This is subverted very nicely in the play as he morphs into Margaret Thatcher, mouthing recordings of her famous nation-rallying speeches. On the opposite side of the stage – both of these human puppets projected onto the back screen – we see General Galtieri. When Thatcher speaks, the words on the surtitles are in Spanish. When Galtieri speaks, in English. Falklands. Malvinas. War. Guerra. Malvinas. Falklands.

The play on language throughout is beautiful – not only the constant swapping between English and Spanish in live and recorded words, surtitled accordingly, but the added wild card of having a Nepalese Gurkha included. His English is still laboured and delivered with a heavy accent. His foreign-ness, his otherness, is presented to us for what it is, another odd twist in this story of colonialism and disputed territory, in which language, and the naming of things, and the power of words, plays such a key part. Many years after the Falklands conflict, we learn, after a long fight for his rights, Sukrim now has UK citizenship.

It is a very clever piece of theatre. You read the blurb, and you think it’s going to be a verbatim piece: three British servicemen and three Argentines from the armed forces, all of whom are veterans of the Falklands/Malvinas war, are brought together onstage. But Lola Arias is far too clever a theatre-maker for mere verbatim. Yes, there are spoken stories, reminiscences presented straight out to the audience, but in this very theatrical piece of theatre, we also get a loud and traumatic drum solo to signify the sinking of the Belgrano; a full-on heavy metal tirade against war; a mock-TV panel show on the alleged eating of ears; and a version of In the Psychiatrists’s Chair.

The interplay between live stage action, found film, and live-feed video is brilliantly executed, using theatrical techniques that Arias collectively calls ‘re-enactment’. Collages of TV news footage from the UK and from Argentina flip by to illustrate or contrast with stories told verbally; newspaper photos that are re-enacted by the very people in those photos, right here and now, in odd little physical theatre vignettes that have a sorrowful look of children playing war games. The re-enacted speeches of the warmongering leaders, the live rock and roll numbers that punctuate the play…

There’s a great balance between hard to stomach moments, and light and playful moments. The drum solo (by Ruben) is an intense and harrowing moment; but it contrasts with the ironic humour of Ruben’s stories about a rather idiosyncratic grasp of English based only on knowing the words to the Beatle songs that Ringo sings. I am the drummer, so I need to know Ringo’s songs, says Ruben – and demonstrates with a charming version of With A Little Help From My Friends. All of this is typical of the lightness that Arias allows into her work, whilst never shying away from the really dark and nasty things that have to be dealt with.

She’s clever, very clever. She leads us in gently, with everyone in jolly reunion story-telling mode. We get cheery accounts of everyone’s basic biographies, and the bare facts of their war experiences. They are all mates now, it’s all in the past. As the play progresses, the stories of what they actually felt when the really horrible things happened emerge slowly, at a pace we can handle. What it really feels like to kill someone. What it’s like to search a dead body for intelligence. What happens when you come home after war and you suddenly haven’t got a job and end up as an addict in a psychiatric hospital. What it’s like to stand in a pub where everyone is singing your praises, but the only person you can talk to is the World War Two veteran at the bar, because they are the only person who has a clue what you’re going through.

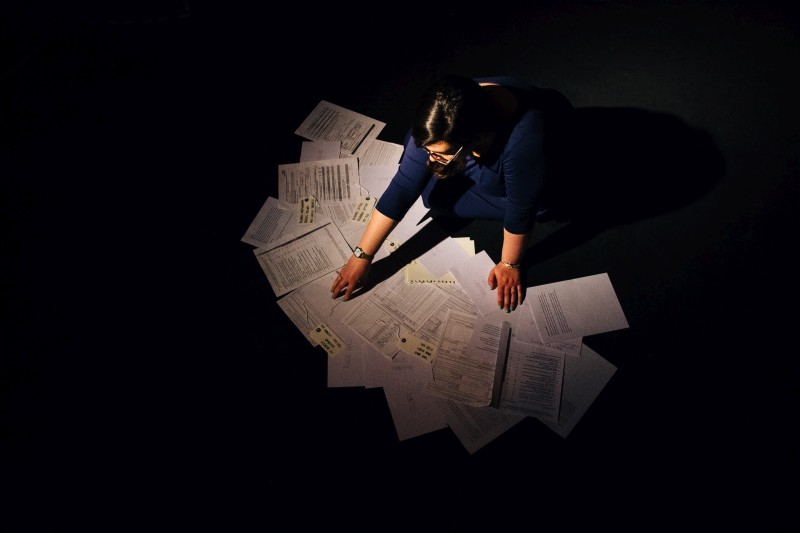

Always, Arias takes care of her audience (as I am sure she takes care of her performers). There is no one onstage other than these six ‘non actors’, who are trusted to carry the play, and do so magnificently. The creation and rehearsal process was long and thorough, and they have worked as a collaborative team to create this extraordinary piece of work. Whatever is needed, they do, these six men who are now one unit, working together on the job. They tell stories of fights and flights, they do press-ups, they operate the live-feed cameras, they dress up, they dress down, they open maps on-camera, they lovingly place a green woollen blanket in shot so that it becomes a mossy landscape, they drag the drum kit on and off, they form a band.

Minefield is not a play about ‘what really happened’ in 1982 in the South Atlantic. It is a play about memory – about what remains years later, about the stories we choose to tell, and about the stories that we discover we have to tell. It is a play about how human beings survive and guard their sanity through continuously interrogating and re-evaluating their memories. It is a wonderful piece of theatre, one that it has been hard to write about, as all I really want to say is: just go and see this, it is brilliant, totally brilliant.

Featured image by Tristram-Kenton

At my girls’ grammar school, the English class of ’72 found DH Lawrence’s descriptions of ‘fecund loins’ and ‘butting haunches’ both hysterically funny and utterly disgusting. For Penny, a college student in The Wardrobe Ensemble’s hugely enjoyable show, Lady Chatterley is a role model, an emancipated woman who ‘wants it as much as he does.’ But Penny (Helena Middleton), like Lady C, is going to be rudely disappointed when her turn comes – or rather fails to.

At my girls’ grammar school, the English class of ’72 found DH Lawrence’s descriptions of ‘fecund loins’ and ‘butting haunches’ both hysterically funny and utterly disgusting. For Penny, a college student in The Wardrobe Ensemble’s hugely enjoyable show, Lady Chatterley is a role model, an emancipated woman who ‘wants it as much as he does.’ But Penny (Helena Middleton), like Lady C, is going to be rudely disappointed when her turn comes – or rather fails to.